Class Session 3

Class Session 3

WEEK #4 (Feb 9, 2012)- BUREAUCRATIC UNIVERSITIES=Leslie Bohon-Atkinson, John Drummond, Cristen McQuillan, Michael Mullin, Casey Van Veen

|

|

| Terms and Definitions for this week |

|

| Bureaucracy (Weber, 1946) |

|

|

= =Professional Bureaucracy (Mintzberg, 1979) |

|

| Reframing Organizations: Structure and Restructuring (Bolman & Deal, 2008) |

|

| Administrative Behavior in Higher Education (Dill, 1984) |

|

Class Notes from 2/9/12

Walkabout - Elements of bureaucracy

What are the main characteristics of bureaucracy?

- Official duties

- Rules of authority

- Qualifications and reviews

- Special type of workforce – want security, well trained, benefits (pension)

- Rigid rules and procedures to follow

- Top-down

- Heavily controlled

How does current context/technology shift Weber’s concepts?

- Organizations must now be more accepting to change

- There is a different type of workforce now who expect different things

- People are less faithful to the company, more faithful to their field

- There is less money to go around, but the qualifications are still heavily expected

- Qualifications can be taken for granted – it is more common for people to be technologically savvy

- Some benefits don’t even exist anymore, some jobs don’t even last 20 years anymore

What is the current role of "education certificates" for work qualifications?

- Depends on the viewpoint

- Human resources love them

- In some cases they are not a good measure of capability

How might a post-modernist view “expert power”?

- May view the experts as people who only have power because we give it to them

Generally speaking, the whole class agrees that Weber’s model is a bit outdated.

Class Debate – Bureaucracy Pros and Cons

Cons:

- Gender roles were different when Weber came up with this theory. Specialized hierarchical power, patriarchal rule. Times are different now. Women understand that to be more powerful they need to have an education. Imbalance of gender roles.

- The stability is definitely not the same as it was when Weber was writing. The same stability can be seen as more rigid and stifling, then secure.

- Rules and policies can impede progress. Companies won’t have the flexibility to grow and change with them in place.

- Too many rules breed complacency, especially at the top. Doesn’t allow the specialization as it used to be. Can become a hindrance for abstract thinking and creative ideas.

- Web of inclusion

- Pigeonholes people, creates people who are only capable of one thing, limited in skill

- A group who is highly skilled can become complacent without the ability to think in adaptive and creative days.

- Today’s age allows more educated individuals with a wider skill set.

- Lateral advantage

- Human resources need to be valued and are often left behind in bureaucracy.

Pros:

- Create clarity and structure out of chaos – form follows function.

- Promotes efficiency, equality, focus large group activity into small set of goals

- Pigeonholing ends up with high quality workers, expertise, history, experience to perform their duties at an excellent level.

- Well designed structure, employees know the rules

- How do you hold a person accountable when they are flexible and not held accountable?

- Experts are highly valuable in their specified fields

- Helpful for the client to know that a structure is in place – gives them security and a chain of command.

Mintzberg

- An example was brought up with the search for the Deans of Arts and Sciences at W&M.

- Technical and administrative support is growing since Mintzberg wrote this article.

- Problems involved mirrored those we are dealing with now (i.e. SOLs)

- More movement, less loyal to the institution, more loyal to the profession

o Higher Ed. is more accepting to this notion than K-12

- How much do we actually know about what others are doing? How do we work together and how do we miss opportunities by not knowing what others are working on?

Second look at case study: Nose to the Grindstone: Hunkering Down Community College

- Financial issues are still at the forefront.

- Re-engineering of the whole organization was done by the new president.

- The president should be aware of past precedent and what was done and accepted in the past.

o Example was brought up of Jean Nichol – taking down the cross at Wren Hall

- Structural approach and authoritative approach are in place.

- Positivist approach also in place – there is one truth.

- There is a question of whether the president really had “buy-in”?

- The organization is very resistant to change – bureaucratic

- In trying to fix a problem, she created new ones.

- Her gender assumptions may have played a part in her actions – she felt the need to be aggressive to assert power.

- Communication needed to be better and more open.

- She was trying to create a professional bureaucracy – others were reluctant.

Dilbert explains some problems with bureaucracy - missing the human element

Summary of readings:

|

Weber, M. (1946) Bureaucracy |

|

|---|

(Note on these notes: I present this more or less as an outline, as the structure of the document is, essentially, a fleshed-out outline with headings intact. The article has no preamble, no applicatory advice, and certainly no fluff; it is highly structured and all business. Weber evidently practiced what he preaches.)

Part 1: Characteristics of Bureaucracy

I. There is a principle of fixed and official jurisdictional areas

- Activities are distributed in a fixed way and bounded by rules

- Authority is distributed in a stable way and is bounded by rules, including powers of coercion

- Provision is made for execution of duties and rights; only the qualified are placed in a position

At the time of the writing (~1900?) Weber notes that bureaucracy only exists in "the most modern" governments and "the most advanced institutions of capitalism" in the private sector. Historically, of course, this has not been the case: even large empires have been run by favored tribunes, nepotism, and cronies with uncircumscribed powers.

II. Principle of Hierarchy

"A firmly ordered system of super- and subordination in which there is a supervision of the lower offices by the higher."

- 10 cent term: an organization that is structured by the One Boss principle is "monocratically organized."

- A bureaucracy is not characterized by being either public or private--the same systems work in either locale.

- "Higher" office is not authorized to "take over the business" of the "lower." "Indeed, the opposite is the rule."

- Once established, an office tends to continue, even when its duty is fulfilled.

III. The "modern" office based on written documents (files)

"There is, therefore, a staff or subaltern officials and scribes of all sorts."

- The official and the staff and files are what make up the eponymous "bureau," or, in the public sector, "the office."

- "...Bureaucracy segregates official activity as something distinct...." - separate from the official's personal home, finances, correspondence, etc. This practice has been developing since the Middle Ages.

IV. "Office management presupposes expert training."

- Bureaucracy is a skill in and of itself, to be learned and valued.

V. "A fully-developed office demands the full working capacity of the official."

- Unlike what Weber seems to view as the old days when "official business was discharged as a secondary activity."

VI. Management of an office/bureau is guided by rules that are more or less stable, exhaustive, and learnable

- Knowing these rules is a skill in and of itself.

Part 2. The Position of the Official

I. "Office holding is a 'vocation.'"

- There are often stringent training requirements.

- The position is construed as a duty, not a position to be exploited for profit (quick, somebody tell Congress!), or even as a "job" for pay--it is acceptance of an obligation in return for a secure existence.

- The official's loyalty is to the enterprise, not to a patron

II. The pattern for officialdom:

- The official is often of high social standing, but this is not always the case. (Note: Weber is almost disdainful of the American habit of elevating successful persons without regard to their formal education, bureaucratic indoctrination, or social status probably because it is less orderly.)

- "Pure type" officials are appointed; even elected officials are appointed by party chiefs to run in the election. Appointed officials are more "technically correct" (in their performance) than elected officials, as appointees are, presumably, selected for prowess.

- Officials serve for life, for the sake of independence.

- Officials receive a salary during their tenure, and a pension in their old age.

- The official's "career" is within the hierarchy.

|

|

| This video provides a brief explanation of Weber's theory of bureaucracy and presents some of the social issues associated with bureaucracy such as psychological problems and zombification. |

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The Professional Bureaucracy

|

Professional bureaucracy is a structural configuration that focuses on standardization of skills. Because professional work is complex, it must be controlled directly by the operator (like a professor or a doctor). The standardization of skills allows standardization and decentralization at the same time! Prime examples of the Professional Bureaucracy – personal service organizations with complex, stable work: schools and universities, consulting firms, law and accounting offices, social work agencies, hospitals. These organizations depend on the skills and knowledge of the operating professionals (the “operating core”) to function. The Basic Structure The Work of the Operating Core – the professionals of this organization are specialists who have considerable control over their work (they work relatively independently of their colleagues, but closely with their clients). Example: professors work mostly alone on their classes and research, but work directly with their clients (students). Coordination is handled through the standardization of skills (which is what their colleagues have learned to expect from them). |

|

Standardization of skills (training) takes a long time – years. The skills become repetitive (like a surgeon knowing how to perform open-heart surgery). What is involved in the training and indoctrination?

|

|

The Bureaucratic Nature of the Structure – one goal of all the training: “internalization” of standards that serve the client. These standards are predetermined through professional associations, which set universal standards. Universities must teach these standards to the future professionals (like K-12 or HE administration).

The Pigeonholing Process – Professionals have certain expertise and the clients’ needs must fit that expertise (pigeonholing). The professional has 2 tasks: 1) to categorize the client’s need in terms of a contingency (predetermined situation, or a “diagnosis”) and to 2) apply that program.

Focus on the Operating Core – The operating core is the key part of the Professional Bureaucracy. Example of a university: The support staff is fully elaborated, but also focused on serving the operating core. The other two parts, the technostructure (like finance and budgeting) and middle line (managers, deans) are thin.

Decentralization in the Professional Bureaucracy – the Professional Bureaucracy is decentralized in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The operating core has the power. The operating core’s power comes from the fact that the work is too complex to be supervised by managers, but the work is in demand.

The Administrative Structure – the professionals seek control of the administrative decisions that affect them (hiring, firing, distributing resources). Therefore, the professionals need control of the middle line (the administrators, managers). How is this done? The professionals are part of the hiring process – they staff the organization with “their own” (p. 56). Deans, VPs, chairs, have to work alongside a committee of faculty.

What is described above is different from the PROFESSIONAL administrators – these are not as powerless as what you see described above. Although the professional administrator does not directly control the professional, he/she “does perform a series of roles that gives considerable indirect power” (p. 58). Those roles are to handle disturbances in the structure (who teaches this biology class? Who should perform that open-heart surgery?) and to serve key roles between the professionals and the outside world (governments, clients).

Strategy Formulation in the Professional Bureaucracy – this is different for the Professional Bureaucracy because it is not so much an organizational strategy, but an individual (personal) strategy held by the professionals, like which clients to serve and how. The strategy has to coincide with professional standards. What’s the administrator’s role in helping the professional with these personal strategies? The administrator helps the professional “negotiate his project through the system” (p. 61).

Conditions of the Professional Bureaucracy –

- The environment is the chief contingency factor. The environment must be complex (complex enough to require the skills used by the professionals) and stable (stable enough to standardize the skills).

- Age and size – not so important – professionals bring their expertise with them. Example: Doctors would do the same kind of work in a big hospital as in a small hospital.

- Technical system is not highly regulating or automated.

Some Issues Associated with Professional Bureaucracy

Problems of Coordination – need of coordination between professional and support staff. Need to coordinate between professionals – this is where pigeonholing becomes a problem. What happens to the patient who falls between psychiatry and internal medicine? (p. 65)

Problems of Discretion – not all professionals are conscientious and competent. Since their work is so specialized, it is not always easy to regulate them. Furthermore, professional associations are reluctant to act against their own.

Problems of Innovation – innovation requires a rearrangement of the pigeonholing AND cooperation with other disciplines. New problems are sometimes forced into old pigeonholes. Innovation requires inductive reasoning and it goes against the way the professional works (with lots of autonomy).

When the above 3 problems happen, there can be a dysfunctional response – external forces (government, clients) try to control the work with direct supervision, standardization of work processes, or standardization of output (Example: SOLs). Complex work is most effective when it’s controlled by the operator; external forces can dampen the professional conscientiousness and innovation.

| Dill, D. (1984). The Nature of Administrative Behavior in Higher Education In this article, Dill reviews research and literature on administrative behavior that developed due to a rapid growth of American higher education after World War II. The review was prompted by three publications: |

|

- Peterson (1974) - extant review of the research literature on the organization and administration of higher education

- Addressed colleges and universities as organizations

- Identified and reviewed growing literature on planning and management techniques in higher education

- Identified that the weakness of literature was due to the lack of empirical studies on administrative behavior or on what administrators actually did

- March (1974) - training of higher education administrators should be based on knowledge of the context of education

- Knowledge should include the nature of education organizations and what educational managers actually do

- Administrative efforts are difficult to improve since they are often unrelated to the ordinary organization and conduct of administrative life

- Mintzberg (1973) - The Nature of Managerial Work

- Original investigations and codification of existing research showed consistent patterns in managerial work

- Patterns went against existing models of administrative behavior that emphasized the rational process of planning, organizing, and controlling

- Research raised questions of whether or not the successful implementation of technologies and processes advocated for contemporary managers was seriously compromised by a failure to understand the nature of managerial work itself

administrative behavior - the behavior of those within the boundaries of organizations who occupy administrative positions

Katz's general managerial framework is linked with Mintzberg's empirically-derived categories.

| Katz |

Mintzberg |

| Human Relations Skills |

|

| Conceptual Skills |

|

| Technical Skills |

|

Managerial Time in Academia

College administrators allocate time similarly to managers of large organizations. College presidents work an average of 60 hours/week, which is at the high end of the scale. However, like managers in other fields, they spend similar amounts of time around their office (30%), in the vicinity of the university (60%), an out of town (22%). They also spend similar amounts of time in contact with others: 1/3 with those outside the organization, less than 10% with trustees, and over 50% with subordinates. Additionally, they spend similar amounts of time alone (25%) and in meetings (40%).

Deans and department heads work an average of 55 hours/week, with 45% of time spent in on administrative work, 9% on research, 16% teaching, and 20% or more in university service. Deans and department heads rate administrative duties as their highest stressor and report that the greatest way to reduce stress would be increasing the hours per week devoted to management.

Human Relations Skill

Peer-Related Behavior: About 30% of college presidents' time was spent with constituents who were not direct subordinates.

Separation of powers:

- Decision-making authority is perceived to reflect a separation of powers.

- Separate administrative culture derives from the specialization of administrative tasks, the nature of associations (with trustees, alumni, and legislature), the visibility and prestige of executive status, and the burden of conveying bad news.

- Department heads have a great deal of influence on personnel decisions, faculty selection and evaluation, salary decisions, dismissal and non-reappointment of faculty, and budget administration.

- Faculty have more influence on student admissions policies, departmental academic standards, and the selection and recruitment of graduate students.

- To reduce separation, managers must build channels of communication and support through informal communication with constituents and use of special assistants drawn from the faculty at large. These "colleague" special assistants are the most influential of all "assistant to" types and serve in a role that is unique to higher education.

Leadership Behavior: The largest block of university presidents' time is spent in contact with direct subordinates, which is perceived as important to administrative success and satisfaction. Job satisfaction is higher when interpersonal behaviors are emphasized over authority relationships.

Faculty attitudes towards department heads:

- Rate satisfaction higher for leaders emphasizing ethical behavior, helpfulness i research projects, accurate and complete communication, frequency of communication, and willingness to represent the interests of the staff

- Prefer tracking research activities in progress through discussion rather than formal reports

- Dislike attempts to restrict the selection of research projects

- Prefer leader to be a "resource person/coordinator" or "facilitator" - one who smoothes out problems and provides necessary resources for research activities

- Support attempts to reward them

Though there may not be an "ideal style" of leadership, highly ranked paradigmatic departments like physics and chemistry tend to have task-oriented leaders, while lesser ranked paradigmatic departments such as sociology and political science are characterized by task- and people-oriented leaders.

Conflict Resolution Behavior: disputes tend to be avoided or muted across all personnel categories - academic administrators, faculty, non-faculty, professionals, and ancillary personnel, as well as community versus institutional personnel. The nature of disputes tended to vary among constituencies:

- Non-professional personnel tended to have conflicts of interest.

- Faculty and administrators generally had value conflicts.

- Administrative disputes were usually settled through compromise or resignation after due consideration.

- Compromise was less common among non-administrators.

- Administrators assumed third party role in conflicts involving other parties, though not as mediators. This was most common in ancillary personnel disputes.

- Administrators tended to impose new arrangements to terminate controversy among ancillary personnel.

- Administrators attempted to optimize the needs of both parties while observing institutional priorities with non-faculty professionals, which disputants saw as another aspect of the conflict.

- The most commonly used conflict management technique was bargaining or splitting differences in an attempt to maximize one's own interest. The second most used technique smoothing or letting people discuss issues in which differences existed without dealing with substantive issues.

- Academic conflict resolution behavior is dramatically different from that in the industrial setting, which most commonly uses confrontation and forcing or power plays.

Conceptual Skills

Information-Related Behavior: the most important information is political information, informal knowledge of constituent attitudes, and academic knowledge. Less important is everyday knowledge of operating information - administrators typically have a 6%-8% error in knowledge of enrollment, faculty size, and finances/budgets. Presidents are most accurate on student-related data and least accurate on faculty data. They most over estimate revenues. Some other notable facts about administrators' information-related behaviors:

- When administrators provide information to guide operational decision-making, it was usually only limited to a due date, guidelines for report format, and individual or group responsibilities.

- While information is critical to administrators, sources and uses of information are unconventional compared to traditional management.

- Administrators' attitudes towards qualitative data varies greatly, though there are three typical responses:

- Use data available on the spur of the moment

- Use interpreters who can understand and translate existing information

- Create parochial or local level information systems

- Administrators tend to value information that has no great decision relevance.

Decision-Making Behavior: as institutions grow and age, decentralization of decision making increases. This is particularly true when growth is accompanied by an increase in academic specialization.

Characteristics of decision-making behavior in college administrators:

- Culture, including local traditions, beliefs, and values, may be a better predictor of locus of decision making than structural variables.

- Decision-making behavior can be influenced by level in hierarchy, distribution of influence, and personal perceptions and attitudes.

- There is little relationship between the nature of the problem and the style of decision making.

- Business techniques are not often used in university decision making.

- In budget and program evaluation decisions, current demand - demonstrated by academic need - is usually the exclusive criteria.

- Patterns of university decision-making somewhat supports the "garbage can" model:

- Decision making frequently does not resolve problems.

- Choices are often made by flight or oversight.

- Decisions are of intermediate importance.

- Demographic factors, influence, personality, beliefs, and technology can affect decision making.

Resource-Allocation Behavior: administrators base resource allocation on perceptions of influence and power. Power, measured by the ability to attract grants and contracts and student enrollments)is the de facto administrative criterion for allocation of scarce resources. Allocation of financial resources is among the highest current priority for change. facilities allocations are usually based on a presidential wish list, and there is little use of class size, teaching load standards, or unit costs in allocation of faculty positions and discretionary budgets.

Entrepreneurial Behavior: managers search their organizations for problems or opportunities for change, then initiate improvement projects to address them. There are two critical assumptions of Mintzberg's analysis:

- The manager is constantly involved in developing and implementing improvement projects and is juggling a number of such projects at one time.

- Many improvement projects fail or lead to no implementable result.

Introspective Behavior: managers need the capacity thoroughly understand their jobs; they should be sensitive to their own impact on their organizations, and they should have the ability to learn by introspection. Professionals learn little from seminars and continuing professional education opportunities; they are most influenced by learning that takes place in conjunction with the job. Academic administrators at the department head and dean levels either resist, deny, or do not fully comprehend the obligations of their administrative duties.

Administrators perceptions of control:

- If administrators perceived themselves in control or as making the major decisions, they spent more time in guiding the growth and development of the department as well as its personnel and programs, and had a greater desire to continue in administration.

- If administrators perceived control to be above them, they typically spent more time working with students, in doing liaison work, and in activities with expected return to the faculty.

Technical Skills

Profession-Related Behavior: According to Mintzberg, the transition fro technical activity to management activity allows for a separation of management behavior from profession-related behavior. However, this transition is rarely completed in the academic environment.

[[Image:Reframing%25204th%2520cover.jpeg| Reframing%204th%20cover.jpeg]]

Bolman, L. & Deal, T. (2008). Reframing Organizations:

Structure and Restructuring

1. Structural Dilemmas

“Tough trade-offs without easy answers”. (p. 73)

- =====Differentiation versus Integration: The more complex an organization, the harder it is to maintain focus.=====

- =====Gap versus Overlap: If roles are too segregated, then certain tasks can fall through the cracks. If roles are too closely aligned, then conflict can arise due to lack of role delineation.=====

- =====Underuse versus Overload: If employees have too little work, they become bored and can be counterproductive. If employees have too much work, morale and quality of work can suffer.=====

- =====Lack of Clarity versus Lack of Creativity: If employees are unclear about what they are supposed to do, they will focus on personal comfort rather than company goals when completing tasks. If employees are too rigidly focused on company goals, their work will lose creativity and the end product will suffer.=====

- =====Excessive Autonomy versus Excessive Interdependence: If employees are too autonomous, people can feel isolated and unsupported. If employees are too tightly linked, people can be distracted from work and waste time on unnecessary coordination.=====

- =====Too Loose versus Too Tight: If an organization is too loose, people will get lost in their work with no sense of purpose or direction. If an organization is too tight, flexibility is stifled.=====

- =====Goalless versus Goalbound: If employees are unaware of company goals, their work may be misdirected. If employees cling too tightly to company goals, the employees may be adverse to change or difference that could positively affect the company.=====

- =====Irresponsible versus Unresponsive: If people ignore company policy, performance suffers. If people adhere too rigidly to company policy, performance can also suffer.=====

2. Structural Configurations

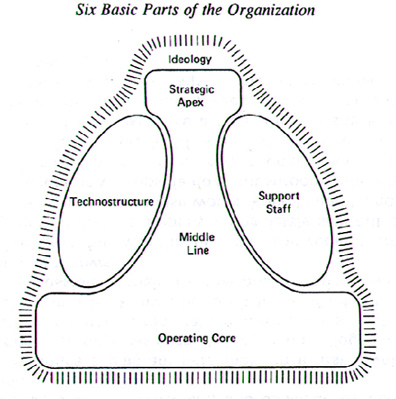

Mintzberg designed visualizations to demonstrate the size and clout of five separate groups as they take form in five different structural configurations. These five groups are:

- {| class="captionBox" style="float: right"

| class="captionedImage" |

|-

| class="imageCaption" | This image includes a sixth part: Ideology. How does ideology affect an organization's structural configuration?

|}

|-

| class="imageCaption" | This image includes a sixth part: Ideology. How does ideology affect an organization's structural configuration?

|}

=====Operating Core – Depicted at the base of each image, the operating core consists of people who perform “essential work” by providing goods or services to consumers such as flight crews in airlines and teachers in schools. =====

- =====Administrative Component – Depicted directly above the operating core, these are managers who supervise, coordinate, and control the operators, such as school principals. This portion of the image includes the Middle Line, which are mid-level managers, and the high-located Strategic Apex, or the most senior directors.=====

- =====Technostructure – Depicted to the left of the Administrative Component, this inclusides specialists, technicians, and analysts who standardize, measure, and inspect outputs and procedures.=====

- =====Support Staff – Depicted to the right of the Administrative Component, this group supports the work of others in the organization, such as secretaries or custodians.=====

Simple Structure

A “Mom and Pop” structure which consists of only two levels: the strategic apex and the operating level. This structure is characterized by:

- =====Direct supervision=====

- =====Flexibility and adaptability=====

- =====Issues with leadership being too closely involved with operating core, causing for distraction by low-level problems.=====

Machine Bureaucracy

Like with McDonalds, a strategic apex makes major decisions and is kept very separate from operating core, with a large middle line, technostructure, and support staff. This structure is characterized by:

- =====Efficiency and effectiveness for routine tasks such as making hamburgers or manufacturing automobiles=====

- =====Consistency and uniformity=====

- =====Tension between middle line and strategic apex=====

Example: In CBS's Undercover Boss, members of the Strategic Apex spend a day moonlighting as the Operating Core.

Professional Bureaucracy

Like within a school, there is a flat structure that consists of a very large operating core with few managerial levels existing between the strategic apex and the operators. There is a large support staff with a very small technostructure. Because the operating core is so large, operators generally perform with little to no direction from leadership, like university professors. This structure is characterized by:

- =====A heavy reliance on training and indoctrination=====

- =====Relative amount of freedom for a large operating core=====

- =====Slow response to change=====

- =====Contention between operating core and strategic apex=====

Divisionalized Form

Like at a university, the majority of the work is done in semi-autonomous units. Each division serves a distinct market and supports its own functional units. This structure is characterized by:

- =====Plenty of resources=====

- =====Power associated with a large-scale organization=====

- =====Contentions between divisions and strategic apex=====

Adhocracy

Loose, flexible structure with ambiguous authority. Most often found in conditions of turbulence and rapid change. This structure is characterized by:

- =====Unclear objectives=====

- =====Contradictory assignments of responsibility=====

- =====Protection from organization taking a position in an “either-or” trap.=====

Helgeson’s Web of Inclusion

An organic architectural form that is more circular than hierarchal. The web builds from the center out, with connections being formed between the center and the periphery. This structure is characterized by:

- =====Entire organization affected when action occurs in one place on the web=====

- =====Requires strong center and periphery=====

- =====Strong community and culture=====

3. Generic Restructuring Issues:

- =====The strategic apex wants to develop a unified mission or strategy so that the organization is easier to control

=====

===== - =====The middle managers seek the opposite of the strategic apex: they want to become less centralized and gain more control over smaller units.=====

- =====The technostructure wants to standardize so that the organization’s progress can be measured using well-defined criteria=====

- =====The support staff wants collaboration so that they can have a stronger influence in the organization=====

4. Why Restructure?

- =====Environment Shifts=====

- =====Technology Changes=====

- =====Organizations Grow=====

- =====Leadership Changes=====

5. Principles of Successful Structural Change:

- =====Reconceptualize the organization’s goals and strategies=====

- =====Study the existing structure and process so that you fully understand how things work=====

- =====Design a new structure in response to changes in goals, technology, and environment=====

- =====Experiment. Keep things that work, and discard things that do not.=====

Example: In Bravo's Tabatha's Salon Takeover, outspoken Tabatha Coffey visits failing salons and helps them to restructure. The above four principles can be seen in her efforts to improve the organizations.

|

"Oh, I forgot, class is over! It was just too much fun!" (Eddy, 2012) |

For further reading:

Olson, G. (2011). "If I Only Knew Then..." from the Chronicle of Higher Education - call for higher education administrators to buck the strict bureaucracy and foster innovation and change.

Goldstein, H., Thorp, B. (2010). How to create a problem-solving institution (and avoid organizational silos) from the Chronicle of Higher Education - good advice for restructuring and keeping an eye on mission.

Cressey, D. (1958). Contradictory directives in complex organizations: The case of the prison. Great description of prisons as machine bureaucracies and professional bureaucracies - suggested by Mintzberg.