Class Session 9

Class Session 9

Decision-Making & PlanningAshleigh, Julianna, Kim, Sean, Tehmina

Abstract

This week’s readings gave an in-depth insight into the complexity of the decision-making and the contextual planning processes through the works of Chaffee, Leslie & Fretwell, Argyris, and Peterson. In her article, Chaffee analyzes the decision making processes and explains why leaders would choose one process over the others. Leslie and Fretwell argue that conflict can never be eliminated and that the situation decides the style of leadership. Argyris's examination of the behavior of 165 top executives led him to discover a number of weaknesses in their interpersonal skills, and his article provides leaders with solutions to these problems. Peterson has made an argument for "contextual planning" as a comprehensive planning strategy that requires multidimensional leadership. The readings-based small-group and class discussions and activities proved to be lively and invigorating. Of particular note was the conclusion that the decision making models provided by Chaffee appeared to align with Bolman & Deal’s leadership orientation models, yet the alignment is not perfect. We need to keep in mind that a group's location in a frame will not necessarily lead to consensus. Personal experiences matter and each person will bring their own understanding. Other lessons drawn from the week’s proceedings were that planning is messy and complex, and that language and definitions are central for reaching shared meaning.

Terms and Definitions

| Concept/Term |

Definition/Description |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bureaucratic Model |

This decision-making model follows a highly structured process that is most effective when applied to routine, often relatively unimportant situations. Due to the unobtrusive nature of the decisions made using this model, this model has rarely been explored by theorists. Please see the overview of Chaffee's Five Models for more information regarding the conditions necessary for the success of the decision-making model, advantages, and disadvantages. |

Chaffee, p. 30-33 |

| Collegial Model |

This decision-making model encourages decision-making through group consensus and is most effective when there is shared responsibility among group members. It is assumed that colleges and universities make most of their decisions according to this model, but while this model may apply to academic decisions, it does not describe the non-academic decisions that cause the greatest problems for administrators. In this model, institutions are directed by faculty, acting as peers who reason together toward their common goals. This model is similar to the rational model in that it has a unifying property. Please see the overview of Chaffee's Five Models for more information regarding the conditions necessary for the success of the decision-making model, advantages, and disadvantages. |

Chaffee, p. 24-27 |

| Decision-Making |

A vast subject, embracing such disciplines as economics, operations, research, philosophy, political science, psychology, sociology, and business police, that as an activity, takes place at various levels and involves such diverse variables as the cognitive capabilities of the decision-maker's mind, the communication of ideas and values among individuals, and the mathematical calculations that are intended to identify the optimal choice. More specifically, the process of making a decision involved choice, process, and change. |

Chaffee, p. 14 |

| Organized Anarchy |

This decision-making model focuses on decisions that are made by accident during times of scarcity and uncertainty. This model is most effective when there is a diversity of goals among group members and time and resources are scarce. Please see the overview of Chaffee's Five Models for more information regarding the conditions necessary for the success of the decision-making model, advantages, and disadvantages. |

Chaffee, p. 33-37 |

| Political Model |

This decision-making model focuses on conflict resolution for decisions to be made and works best when there is negotiation among members involved. This model is most commonly seen in inter-departmental decisions and and there is a believe that the members involved in the decisions have multiple conflicting values and objectives that are determined primarily by their self-interests. Please see the overview of Chaffee's Five Models for more information regarding the conditions necessary for the success of the decision-making model, advantages, and disadvantages. |

Chaffee, p. 27-30 |

| Rational Model |

This decision-making model is the ideal model as it emphasizes the uniqueness of every situation and the members involved. This model works best when there is common goal or set of goals among the members involved and there is a plethora of time to work through the decision-making process. Please see the overview of Chaffee's Five Models for more information regarding the conditions necessary for the success of the decision-making model, advantages, and disadvantages. |

Chaffee, p. 20-24 |

| Benchmarking Studies |

Leslie and Fretwell explain that these are studies that use data to assess their own performance in comparison with peer institutions (p. 112). The authors point out that these studies would not be useful in the manufacturing sector because one cannot compare peer institutions. For example, William and Mary (WM) and the University of Virginia could engage in benchmarking studies to determine rates of alumni giving as they are both public universities albeit with vastly different student enrollments. |

Leslie & Fretwell, p. 112 |

| Presidential Leadership |

Leslie and Fretwell explain that presidential leadership was a factor in all of their site institutions as they studied crises management. Presidential leadership is a specific delivery and style to an institution’s key leader. For example, President Reveley and former WM President Gene Nichols had very different presidential leadership on the WM campus. |

Leslie & Fretwell, p. 115 |

| Process Fatigue |

Leslie and Fretwell allude to “process fatigue” (p. 117-118) as the deluge of bad news and constant budgetary pressures on an institution. “Process fatigue” has the effect of wearing down an institution and destroying its morale. In times of crises, this is very important to guard against because an institution’s stakeholders can only take but so much gloom. |

Leslie & Fretwell, p. 117-118 |

| Resilient Universities |

Leslie and Fretwell’s idea of the best type of university mindset in a time of challenge and crisis. “Resilient universities develop clear values, programs that add value to students, and measures of progress toward achievement of outcomes.” (p. 132) For example, Virginia Tech would be seen as a "resilient university" after sustaining the campus shooting tragedies. |

Leslie & Fretwell, p. 132 |

| Simultaneous Tracking |

Leslie and Fretwell’s term for a “way of dealing with separate components of a problem nonsequentially, nonhierarchically, and in a nonlinear way” (p. 127). This is an important method of conflict management at a university level that discourages a stagnant response. For example, this method could be used if a university faced severe budget cuts at the same time it faced low enrollment and bad press. |

Leslie & Fretwell, p. 127 |

| Contextual Planning |

A process for creating/shaping external contexts that favor the institutional mission and designing internal contexts with new institutional roles. This approach can incorporate either or both of the other two types of planning. Looks at the changing nature of the industry to identify potential new roles and relationships, and then shape environmental conditions and institutional arrangements to be more competitive in the new industry. Peterson suggests that this approach is best for situations in which the nature of an industry is in flux and can be influenced by the institution. For example, as financial resources continue to diminish for higher education, institutions have begun working with the external environment to create partnerships and agreements with businesses and other industries to create their own funding sources. Some of this is done at the institutional level, some at departmental levels, and some at the individual level as the research university seeks alternative funding sources. As universities successfully do research or fill other roles for outside organizations they change the external environment's view of higher education and build additional support for their programs. |

Peterson, p. 136-137 |

| Long-Range Planning |

Forecasting resources and trends of the future, making plans based on the predictions, following through on the plans, and continuously assessing those plans; Peterson suggests that this is an appropriate approach in times of stability. For example, long range models that look at the number of eighth graders in the population, project how many of them will be in college in six years and make a plan. Such planning assumes that the trends of the past will continue and that there will be little change in the college population over time. |

Peterson, p. 134-135 |

| Strategic Planning |

Assesses current and future environmental situations as well as strengths and weaknesses of the institution, looks for comparative advantages, finding a strategic niche. Peterson suggests that this is appropriate when external factors are beyond the institution's control and it must adapt to external pressures. For example, as higher education has become increasingly global, strategic planning has helped campuses focus on diversifying and preparing themselves to compete in a global market. |

Peterson, p. 135- 136 |

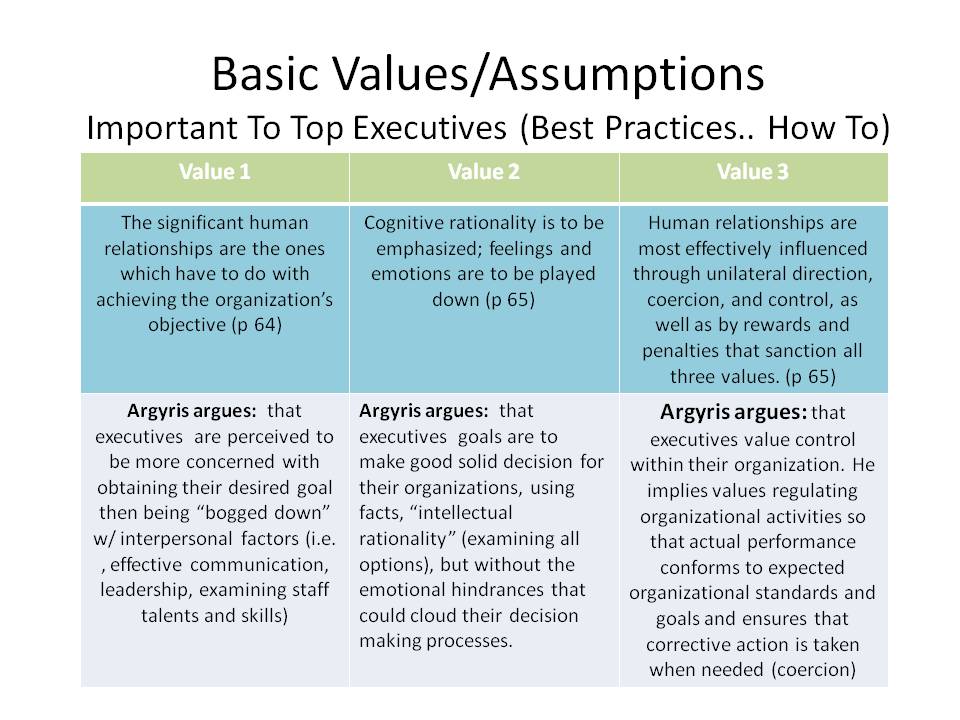

Antagonism |

a principle (philosophy) where opposing groups openly express their dislike towards one another regarding a group behavior or actions. Argyris uses this concept of antagonism to show the fragile relationship between the executives and middle managers. |

Argyris, p. 78-79 |

Decentralization |

a principle (philosophy) where, decision making authority is dispersed into smaller units within an organization. Argyris briefly reference this concept in this article by showing how upper management (board) involvement (intervention) in departmental issues can lead to morale and trust issues. |

Argyris, p. 80 |

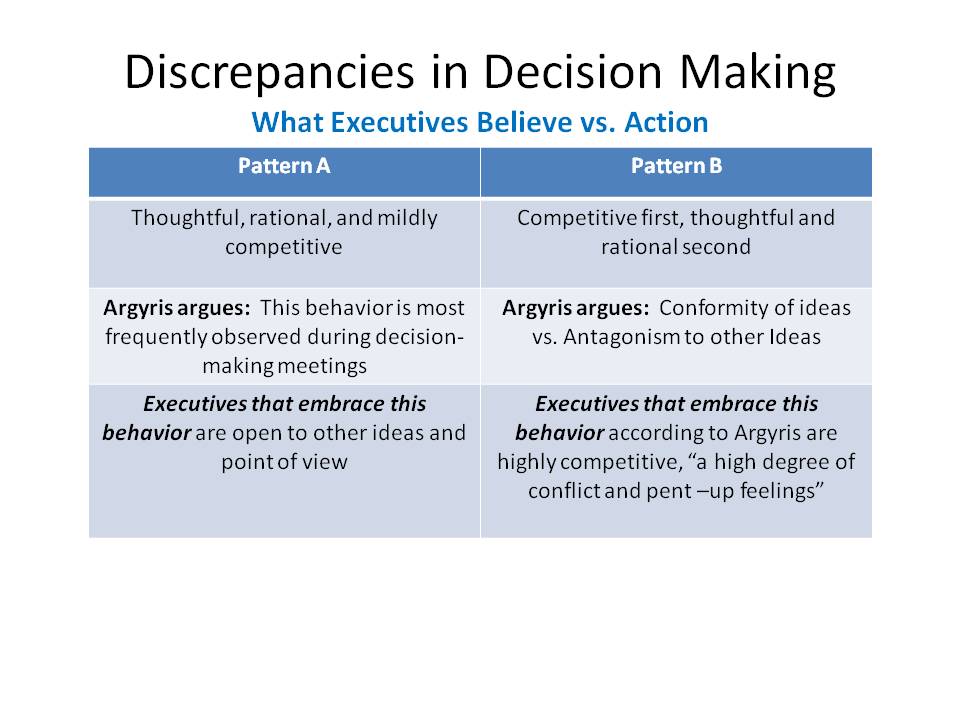

Pattern A |

explores the behavior characteristics of leaders (executives) during decision making situations. Argyris argues that executives that embraces this pattern are often “thoughtful, rational and mildly competitive”. Executives that emulate Pattern A behaviors are often open to others ideas, as a means to discount their ideas credibility. |

Argyris, p. 61 |

Pattern B |

also explores the behavior characteristics of leaders (executives) during decision making situations. Argyris argues that an executive that embraces this pattern are “competitive first and thoughtful and rational second”. Executives that emulate Pattern B behaviors are often dealing with conflict and trust issues (antagonism). |

Argyris, p. 61-62 |

Risk-Taking |

Argyris defines this term as "any act where the executive risks his self-esteem. This could be a moment, for example, when he goes against the group view; when he tells someone, especially the person with the highest power, something negative about his impact on the organization; or when he seeks to put millions of dollars in a new investment.” |

Argyris, p. 60 |

"Life is the sum of all your choices" ~ Albert Camus

Summary of Class Discussion

Announcements:

- No class on 19 April

- Case studies are due by 8 p.m. on 19 April

- Group cases will be located in the information tab on blackboard

- The international comparative rubric has been updated

- The Hickman article has been updated

Activity 1:

At the beginning of class, sixteen discussion questions based on this week’s readings were helpful prompts for a lengthy small group discussion. The first question explored the context of the era of the 1980s in shaping Chaffee's thinking about decision making. It was observed that when Chaffee wrote the article, the concept of strategic planning was still new. Coupled with the development of leadership theory, strategic planning was transitioning from "hero leadership" to other theories. This was an era that saw unionization across [[/| community college] campuses and there was a real need to think of the processes instead of just unilateral decision making. The era was also at the cusp of the development of concept of shared governance. In this context, Pam pointed out that some courses in the EPPL program like EPPL 603 (Leadership in Education) are helpful in understanding how decision making theories historically align with leadership theories.

In response to the question regarding logic in university decision-making, one group linked up this week's readings with [[Class Session 8| Crellin]'s reading from the previous week noting his observation that the decision making process is often more important and meaningful to the participants than the decision itself.

During the discussion of whether collegiality is still alive in academe, all members in one group were unanimous that it is indeed viable in academe though most often among the faculty but not so much among administration. Often the collegial and bureaucratic models parallel each other in universities.

Activity 2: Building on Chaffee’s Five Models

After taking a break, the class was broken into Bolman and Deal leadership orientation groups and addressed the following questions:

1) What decision-making model seems to make the most sense?

2) How might you approach planning given your organizational framework?

3) What stakeholder groups/other voices get heard in this instance?

4) What are the potential blind spots?

Pam encouraged the class to adopt a “gestalt” viewpoint. It was pointed out that the models were not as clear cut as the class may assume at the outset. For example, for the structural group the bureaucratic and the structural models did not align. Pam pointed out that there may be similar language and labeling; however, we cannot necessarily force a model to fit the labeling. Each person will bring their own understanding to the model.

In response to question 2, the HR groups decided on delegating decision making as their preferred approach to planning. The structural group settled on rational and logical planning. While for the political group, persuasion was a big part of the planning process.

Activity 3: "Cutbacks and Priorities" case analysis

The class continued in the small leadership orientation groups. Next, passionate advocacy and negotiation ensued. Each small group discussed the issues and came to a consensus. The most salient points from the discussion were as follows:

- The political group decided to cut out faculty and staff pay and not comply with ADA.

- The structural and Human Resources (HR) group came to the same conclusion and they cut out multicultural and emergency medical.

- HR group #2 decided to cut out emergency medical services and faculty salary increases.

- Policy #7 offered the political group an opportunity to develop shared meaning about the term "facilities."

- Pam commented upon the notion that how someone defines a term matters.

- In HR group #1, John redefined “conflict” for the group.

- Pam observed that we all come from our own locations and frames and that every person brings their past into decision-making. Time, context, and our environment also matter in decision-making.

Pam encouraged discussion on tactics used in reaching a consensus within our small groups. Language was again very important. For example, Terry mentioned that wording such as “terminate” matters. By defining this term, “critical needs” changed in priority. In the political group, the art of persuasion was employed. Sean framed the medical aspect differently by asking, “Which one (the campus emergency medical services or the local hospital) would bring revenue?”

Takeaways:

- Data–driven decision-making is persuasive. Pam remarked that data can be used to call someone’s bluff at a meeting, to delay a decision, and finally to bolster an argument.

- The experience of shared decision captured in one sentence: shared language and assumptions matter as people execute decisions.

Quote of the day: "You go, girl!"

--Argyris to Chaffee

(Okay, he didn't say it but our group thought he might in response to the question "Consider what Argyris might say to Chaffee...")

Summary of Readings

Chaffee: Five Models of Organizational Decision Making

| Ellen Chaffee |

Chaffee (1983) writes that "decision-making itself is a vast subject, embracing such disciplines as economics, operations, research, philosophy, political science, psychology, sociology, and business police. As an activity, it takes place at various levels--individuals, collective, group, and organizational--and it involves diverse variables as the cognitive capabilities of the decision-maker's mind, the communication of ideas and values among individuals, and the mathematical calculations that are intended to identify the optimal choice," (p. 14). In her paper, Chaffee seeks to break down the decision-making processes and explain how and why an organization would choose one process over another.

Introduction/Background

Five patterns of decision-making that emerged through research and are now known as organizational decision models are:

- Collegial: Deciding by Consensus

- Bureaucratic: Deciding by Structured Interaction Patterns

- Political: Deciding through Conflict Resolution

- Organized Anarchy: Deciding by Accident

- Rational: Deciding by Reasoned Problem-Solving

Chaffee points out that not all of the models are widely accepted as true reflections of organizational behavior. For example, the rational model is often criticized as unrealistic, but nonetheless, the rational model has been selected by virtually everyone who engages in planning as the ideal decision-making process. As a result, Chaffee seeks to demonstrate the ways in which the rational model can occur and can be used as an advantage by administrators (p. 15).

Administrators are resistant to applying management theories for several reasons (p. 15):

- Management theories seem to be overly complex

- Management theories tend to be applied only after action is taken

- Management theories do not reflect an administrator's individual management style

- Management theories seem unrealistic and cumbersome

- Administrators are too busy making a never-ending stream of decisions to analyze past decisions

- Administrators may see no good reason to analyze past decisions

- General management theories/models may seem particularly useless since administrators feel that their personal decision processes are essentially rational, yet must be modified to suit each specific situation

Three counterclaims to administrators are (p. 16):

- Although models may seem complex and abstract, they have been shown to reflect reality

- Analysis of the ways in which organizations make decisions, as distinct from the decisions themselves, can be very useful

- Decision theories at the organizational level of analysis deal with quite different phenomena than decision theories at the individual level, and these phenomena can be structured in the organization so that they promote a desired decision process regardless of the specific situation

Important Notes Related to the Counterclaims:

- Complexity arises because real decision processes often exhibit elements from several models

- Theories seem to include more elements within each of them than a real process shows--the process may have some elements of one model, some of another, and some that seem to correspond to no model

- Life is not as tidy as the models imply

- Research has shown that decisions may be made primarily on the basis of objective reason, consensus, routine or custom, relative power, coincidence, or some combination of these factors

The Decision Process

- The process of making a decision involves choice, process, and change

- Though the need to make a decision may arise form forces that are beyond administrative control, the decision is, by definition, controllable

Choice

- The organization has a choice among many alternative courses of action

Process

- Process is used quite deliberately to emphasize that decision-making is active (it involves interactions among people and requires time)

- Process begins with the apparent need for a decision and continues through the decision itself to its effect on the organization

- The results of the choice and consequent feedback become part of the process, producing either reinforcement or modification of the decision

Change

- The result of an organizational decision is a change in the organization

Underlying Features of Decision-Making Include:

- The values of the organization and the actors within it

- The alternative courses of action considered

- The premise directing the consideration of alternatives

| Elementsofchoice.jpg |

Overview of the Five Models

| Model |

Conditions Necessary for Success |

Advantage |

Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bureaucratic |

|

|

|

| Collegial |

|

|

|

| Organized Anarchy |

|

|

|

| Political |

|

|

|

| Rational |

|

|

|

Bureaucratic Model

Due to the unobtrusive nature of the decisions made using this model, this model has rarely been explored by theorists. This model is most effective when applied to routine, often relatively unimportant situations (pp. 30-32).

| Bureaucraticmodel.jpg |

Collegial Model

It is assumed that colleges and universities make most of their decisions according to this model, but while this model may apply to academic decisions, it does not describe the non-academic decisions that cause the greatest problems for administrators. In this model, institutions are directed by faculty, acting as peers who reason together toward their common goals (pp. 24-27).

| Collegialmodel.jpg |

Organized Anarchy

This decisions made through the use of this model tend to happen through accidents of timing and interest.

| organarchy.jpg |

Political Model

This model is commonly used when approaching interdepartmental decisions. Conflict resolution is the basis for this model and there is a believe that the members involved in the decisions have multiple conflicting values and objectives that are determined primarily by their self-interests. This model allows for members to work out their differences through negotiation (pp. 27-30).

| Politicalmodel.jpg |

Rational Model

This model, though some may believe it is unrealistic, is considered to be the ideal model for decision-making (pp. 21-24). This model is inherent in the economic theory of the firm, the scientific method, and in such prepackaged management tools as Planning-Programming-Budgeting Systems and Management by Objectives.

| Rational_model.jpg |

Leslie & Fretwell: Decisions and Conflict

| class="captionBox" style="float: left" | |

| David W. Leslie |

| {| class="captionBox"

| class="captionedImage" |

|-

| class="imageCaption" | E. K. Fretwell Jr.

|}

|-

| class="imageCaption" | E. K. Fretwell Jr.

|}

| CONTEXT: Leslie and Fretwell interviewed several people at various “site institutions” to collect the below mentioned information. Two of the sites that they explicitly mentioned were Bloomfield College and Trenton State College, both in New Jersey.

|}

Important salient points from the article:

- Fiscal stress and conflict affect decision-making (p. 107)

- The chapter covers the following: (p. 108)

- Decision making during fiscal crises

- Defining the situation and promoting understanding

- Ownership of and commitment to the institution

- Balancing leadership and involvement in decision making

- Consistency of environment

- Internal communication

- The emergence of conflict over strategies

- Use of “simultaneous tracking” in adapting to stress

- The CEO’s role in simultaneous tracking

Decision Making in Crisis (pp. 108-110)

- Fiscal crises tends to shift the burdens of decision making to CEO/key leaders

- With scarcer resources, authoritative decisions were inescapable This process shortens the distance between the top and bottom of a campus hierarchy

- Point to Ponder: What happens when the leader is not authoritarian?

- President, VP, Deans, Department Chairs may have less clout now and less freedom to produce independent analyses and plans

- If the situation produces a President who tightens control, “the middle management” has less discretion and freedom

Defining the Situation and Promoting Understanding (pp. 110-113)

- Honesty is necessary in this step

- A CFO stated: “ . . . .People will pitch in and help if they know what the problem is. You have to know how much of a hole you are in before you can devise a way to get out of it.” (p. 111)

- Students were the most difficult to convince that the budget needed to be cut whereas understanding of the crisis was clearest at the institution’s top leaders

Ownership and Commitment (pp. 113-115)

Point to Ponder: Leaders need to be cognizant of creating and establishing shared meaning for their stakeholders so that their message is clear to all audiences

- Communicating budgetary and financial information and data is challenging

- Trustees and alumni leaders conceded much in decision making to the top leaders because they are usually volunteers

- The central administration communicates the big picture of the institution

Balancing Central Leadership and Communal Involvement (pp. 115-118)

- Communication strategies were all generally similar at the various sites

- The three common steps that the institutions took were (p. 116):

- Redefining the situation

- Sharing Financial data

- Promoting understanding of the implications

- At all of the site institutions, the CEOs carried the burden of communicating and dealing with the media and other public relations responsibilities

- The CEOs understood their institution’s strengths and weaknesses

- The CEO was in a position to “orchestrate whatever responses the institution might make” and this became the most difficult part (p. 116)

- Leaders must not drain the institution with too much bad news or else the result could be low morale and “process fatigue” (see Terms section above)

Consistency of the Environment (pp. 118-120)

- If the environment of the institution is always changing, the problem becomes very difficult to “frame”

- The authors cite Mintzberg stating: “organizations need strategy to set direction, focus effort, define the organization, and provide consistency” (p. 119)

- Point to Ponder: Can you think of an organization in 2012 that does not have a clear focus?

- Point to Ponder: Is Mintzberg really saying that an organization needs a vision and mission statement?

- The authors conjecture: “On one hand, some mix of strategy, opportunism, and continuous adjustment to turbulence—if guided by an enlightened consensus among key stakeholders—is the most likely path to realistic change” (p. 120)

Internal Communication (pp. 120-122)

- An institution needs a “structured and consistent message” or else a “free-floating opportunism” may persist (p. 120)

- From many voices on the campus, one message must reign

- Small successes should be recognized

Conflict: The Shape of the Field (pp. 122)

The authors observed the following when an institution was facing fiscal issues and found that the institutions were able to:

- Develop forums in which ideas could be explored

- Realistically assess their market and their role

- Consider the needs of their clienteles and communities

- Develop and nurture creative program ideas

- Open themselves to partnerships, external support, and involvement of students and other stakeholders

The following points are important to embracing crises (pp. 122-127):

- Breaking with the Past

- Faculty Responsiveness

- Process

- Open/Closed: How is the change process is perceived by individual stakeholders? Open would be viewed as favorable and would be the path of least resistance.

Key takeaways:

- Planning is important!

- Conflict will always be a part of any decision-making process

- When “subunits” of an institution work together, the greater health and well-being of the whole university is promoted (p. 129)

- Leadership styles will vary depending on the situation at hand

- The authors hope to “convince trustees, administrators, and faculty alike that they should learn from others’ experiences” (p. 131)

Return to Terms/Concepts

[http://www.amazon.com/Wise-Moves-Hard-Times-Universities/dp/0787901962

Peterson: Contextual Planning

| Marvin W. Peterson |

Peterson, M.W. (1997). Using contextual planning to transform institutions. From Planning and management for a changing environment: A handbook on redesigning postsecondary institutions. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey Bass.

Contextual Planning: A new strategy for planning: more appropriate for turbulent environments, proactive, has the potential to be transformative, anticipates macro change, is an extension of long range and strategic planning approaches, impacts internal and external relationships, is comprehensive, and requires multidimensional leadership.

The Historical Evolution of Planning Approaches: A Contingency Model

Postsecondary institutions have only been engaged in planning since 1950.

1950s: campus and facilities planning in response to increased enrollment

Late 1960s – early 1970s: financial and resource planning needed due to leveling enrollment andeconomic factors

Mid-1970s – early 1980s: enrollment forecasting and academic program planning due to constraints on enrollment demand and financial resources as well as institutional competition for resources

Mid 1970s +: comprehensive planning occasionally used when broader efforts were required

When applying a contingency view to planning, you see that external forces drive how planning needs to be done. This provides a model for understanding various planning approaches, namely, long-range, strategic, and contextual approaches and their development.

1950-1975: Plans, Forecasting, and Long-Range Planning

1950-1960s context: expansion in U.S. higher education, financial support from government, public support high

Pressures: clear sense of direction for growing institutions, the need to account for expanding resources (necessary to keep public support).

Changes: Two models of organization arose during this period:

- Bureaucratic organization – focus on building structures and mechanisms

- Collegial model – faculty, students, and constituents all within a community of learners

Performance: quantify resources to justify spending

Planning: create master plans for the institution to justify resources and guide development

Late 1960s context: low satisfaction with large, impersonal, structured institutions; Vietnam War and Civil Rights Movement

Pressures: campus control of students, increase access for minority students

Changes: higher education institutions seen as open systems (no longer closed) and as political organizations with competing constituencies

Performance: ACE sponsored studies focused on performance largely through peer review

Planning: short-term, responsive, contingency planning common

Early 1970s context: economic recession, end of baby boomer generation, 1972 Higher Education Amendments reallocating financial aid to students, not institutions

Pressures: Need for efficiency, new student markets, more planning

Changes: New models were either comprehensive, information based management models or market-oriented

Performance: a new focus on results, quantitative measures of productivity and efficiency

Planning: forecasting important, long-range planning with constant revision, planning became an administrative role on campuses

1975-1990: Strategic Planning

Late 1970s -1980s context: economic challenges continue, forecasts suggest a new college student in the future (background, ethnicity, financial status), changing demand, waning public support

Pressures: more competition between higher education institutions; need to be more effective and efficient

Changes: models focus on flexibility and decentralization; organized anarchies and matrix models appear; higher ed. institutions now strategic organizations in need of a niche

Performance: criticism of education at all levels K-16, desire of policy makers for performance measures focused on student learning outcomes

Planning: strategic planning

*Moving into the 1990s, there are two themes 1. External challenges are playing a significant role in shaping the internal elements of higher education 2. Old models, approaches, and criteria are not replaced by new ones, but part of the big picture in order to understand governance, performance, and planning patterns

The 1990s and Beyond: Contextual Planning

Context: changing societal conditions related to diversity, technology, assessment, globalization, etc.; new organization types, new technology for learning, working relationships move from that of service provider to collaborator/competitor, resources stretched as financial resources are reduced, a new student base develops, continued loss of public support to higher education

Pressures: increased competition, turbulent environment (undergoing many changes)

Changes: new models increase the complexity of the university, which is now seen as a conglomerate or network organization; the view of organizations as cultural entities is on the rise

Performance: new criteria for performance focus on mission, external relationships, and institutional culture

Planning: contextual planning – broad, flexible approach; holistic, focus is on redesigning the internal and external context

Contingency Revisited

Planning approaches are influenced by changes in complexity and competition as well as changes in turbulence in the environment

External Perspectives

| Planning Approach |

Environmental Assumptions |

Organization-Environment Dynamic |

Institutional Strategy |

Planning Process |

| Long-range planning; “responsive” |

Predictable sectors and resource flows |

Responsive, rational |

Limited competition, adjust plans to reality |

Assumptions, forecasts, and plans |

| Strategic planning, “adaptive” |

Conflicting sectors and resource flows |

Adaptive, judgmental |

Post-secondary education competition, comparative advantage, “fit” or “niche” |

Institutional mission, image, and resource strategies |

| Contextual planning; “proactive” |

Complex but malleable |

Proactive, intuitive |

Cross-industry cooperation, coalition, or competition |

Redefine institutional role, mission, and external relationships |

Peterson, p. 134

Internal Perspectives

| Planning Approach |

Organizational Planning Focus |

Motivation Mechanism |

Mode of Control |

Member Behavior |

| Long-Range planning |

Purpose/policies, goals/objectives (formal organization) |

Direction and control |

Inputs, preaudit (assessing need for resources) |

Constrained behavior |

| Strategic planning |

Program and resource allocation strategies (resources) |

Guidance, review, and improvement |

Outcomes assessment, postaudit |

Flexible behavior |

| Contextual planning |

Direction, values, process, and meaning (organizational culture) |

Themes and visions |

Sense of direction, involvement, and ownership |

Empowered behavior |

Peterson, p. 135

Three Planning Approaches: Elaborating Contextual Planning

Long-Range Planning

| What it is |

Key questions |

Assumptions |

Focus |

| Forecasting resources and trends of the future, making plans based on the predictions, following through on the plans, and continuously assessing those plans. |

“What can we achieve in this environment?” “How can we get there?” |

External environment controls what can be achieved. Stability of resources and enrollment. |

Forecasts Environmental assumptions Plans direct/control institutional behavior Clarification of purpose and goals, policies and procedures |

Adapted from Peterson, p. 133-134

Strategic Planning

| What it is |

Key questions |

Assumptions |

Focus |

| Assesses current and future environmental situations as well as strengths and weaknesses of the institution, looks for comparative advantages, finding a strategic niche |

“How can we modify the institution to be a more effective competitor within our environment and our industry?” |

Most of the environment is outside the control of the institution Organization is loosely coupled |

Looks for possibilities and threats. Adapt mission, purpose and function to the environment. Competition in an environment that is less predictable and more complex. Compares self to other institutions looking for a comparative advantage. Focus on results. |

Adapted from Peterson, p. 135-6

Contextual Planning

| What it is |

Key questions |

Assumptions |

Focus |

| A process for creating/shaping external contexts that favor the institutional mission and designing internal contexts with new institutional roles. Can incorporate either or both of the other two types of planning. Looks at the changing nature of the industry to identify potential new roles and relationships, and then shape environmental conditions and institutional arrangements to be more competitive in the new industry. |

Environment and industry can be influenced. Institutions can change their most basic elements. Relationships in and beyond the higher education industry are interactive, complex, and changing, but malleable. |

Proactive planning. Look at the nature of an industry and what shapes it to understand how it is changing and what new relationships are developing. Intuitive choices are necessary, as are rational decision making and strategic judgments. May need to redesign or reorganize primary functions and structures to adapt to a new role or mission. Culture is important, and members must reform their behavior and values (which requires buy in). Members are motivated to change by a vision of what can be. Empower members with a role in decisions, incentives, and support. |

Adapted from Peterson, p. 136-137

A Process View of Contextual Planning

Contextual planning summary: planning approach for situations in which the nature of an industry is in flux, mission and role of an institution are being questioned, and the institution must transform itself. It starts with an assessment of what is changing in the external environment, of the change happening in the postsecondary industry, and of the institution itself.

Planning issues are related to the redefinition, redirection, redesign, and reform of the institution. The process is made up of 7 elements which together guide contextual planning:

- Insight: in higher education this is an understanding of the dynamics involved in the shift from “an industry of postsecondary institutions to a postsecondary knowledge industry” (p. 139-140). That is to say, to understand all the forces of change involved even before you know what the result will be and use the information to “gain a perspective on where the emerging knowledge industry is heading” (p. 140). New insight emerges out of the challenges to the existing industry and the emerging knowledge industry. This information is used to define and reshape the new industry and reshape the institution to fit it.

- Initiatives: a sense of direction, essential in a changing industry to avoid becoming obsolete; initiatives imply significant changes, but don’t say exactly how they will be made; provides a vision for the institution; key: must be perceived as attainable and members need to be able to participate in making it happen

- Investment in Infrastructure: assumes that if the industry is in flux then there are multiple program elements that should change, requiring investments of resources that support the development of ideas and programs that are seen as consistent with the initiative; the goal is to make investments that are visible and important to supporting the initiative

- Incentives: to encourage members of the community to participate in program development and make the changes necessary to support the initiative; need incentives that are substantive (money) and those that are psychological (praise); key to increasing participation in the initiative

- Involvement: need many opportunities to get involved as well as opportunities for improvement of self (new skills, training, etc.); investment and incentives should lead to increased involvement

- Information: needed by internal and external constituents; should be widely disseminated telling the what and why of the initiative, what is being invested into it, how it will improve the institution, and what the incentives are

- Integration: need to assess the activities that are supporting the initiative and reinforce those efforts that are successful and integrate those that are effective into the organization; “contextual planning…designed to create new initiatives in an uncertain and rapidly changing environment, placing a greater emphasis on stimulating movement than on carefully directing planning” (p. 143)

Implementing Contextual Planning

A paradigm shift: perspective, change, and thinking

Success requires a paradigm shift for leaders and participants at 3 levels:

- Cross-industry knowledge perspective: the emerging industry is ill defined and must be understood through the changes occurring in the current industry. At the same time, one must look across related industries at their interactions and where they overlap.

- Change orientation: moves away from individual or program change toward macro change at the industry or institutional levels

- Contextual thinking: must develop an holistic understand of one’s internal and external positioning in the environment and the dynamics between these environments; emphasis is on reshaping the external environment and the internal design and function of the institution

Primary challenge of contextual planning: moving the institution to focus externally on how the industry is changing, what role the institution should play in that change, and internally, how does the institution redesign its basic processes and structures

New Models of Organization and Performance

“Network” or “interorganizational network” model: fluid network of collaborative arrangements - unbounded research linkages, relearning enterprises, learning networks, global institutions, etc.

“Conglomerate” model: develop a core identity for the institution with autonomous units

“Organization as culture” model: organizational culture (beliefs of what the institution is all about) is critical for two reasons 1. Is a reason to resist change 2. Is a focus for cultural reform Both reasons require careful management.

Macro Change

Changes at varying levels of the institution should be integrated. Levels include structural, cultural, and behavioral. Contextual planning is a multilevel and comprehensive strategy for change.

Assessment

Broad assessment needed in contextual planning. Examples include assessing the external environment – the industry as a whole and related industries that could become linked (Such possibilities of linkage must be assessed to determine the implications of such a connection.) and the internal environment – redesigning and restructuring require pre – review of the options as well as post – reviews of the changes. Additional assessments should be made of the capacity for change within the institution and the changes to the culture within the institution.

Paradox: Change and Consistency, Conflict and Commitment

Long term commitment and consistent efforts are necessary for major changes to occur.

Significant change is likely to lead to conflict between constituents as well as between value systems. Persistence through such conflict can lead to stronger commitment in the end.

Resources and Risk

Contextual planning depends on a substantial amount of flexible resources. Also requires risk – must be willing to assess and face risks throughout the process.

Leadership: A Complex Process

Multidimensional leadership is necessary. Must be broad leadership with a future orientation. Leadership is required at multiple levels, internally and externally. A team of leaders is likely most effective.

Four leadership types for contextual planning:

- Transformational leadership – provides the vision and the initiative(s)

- Strategic leadership – clarifies new relationships and reorganization, provides strategy for making needed changes

- Managerial leadership – realign programs, policies, etc.

- Interpretive leadership – links major changes to the everyday tasks of faculty and administrators and what the change means to them

| Chris Argyris |

Argyris: Interpersonal Barriers to Decision Making

|

=Study Overview= Argyris examines the behavioral patterns of 165 top executives (board members,executive committee members, and upper managers) composing of some 265 meetings.

|

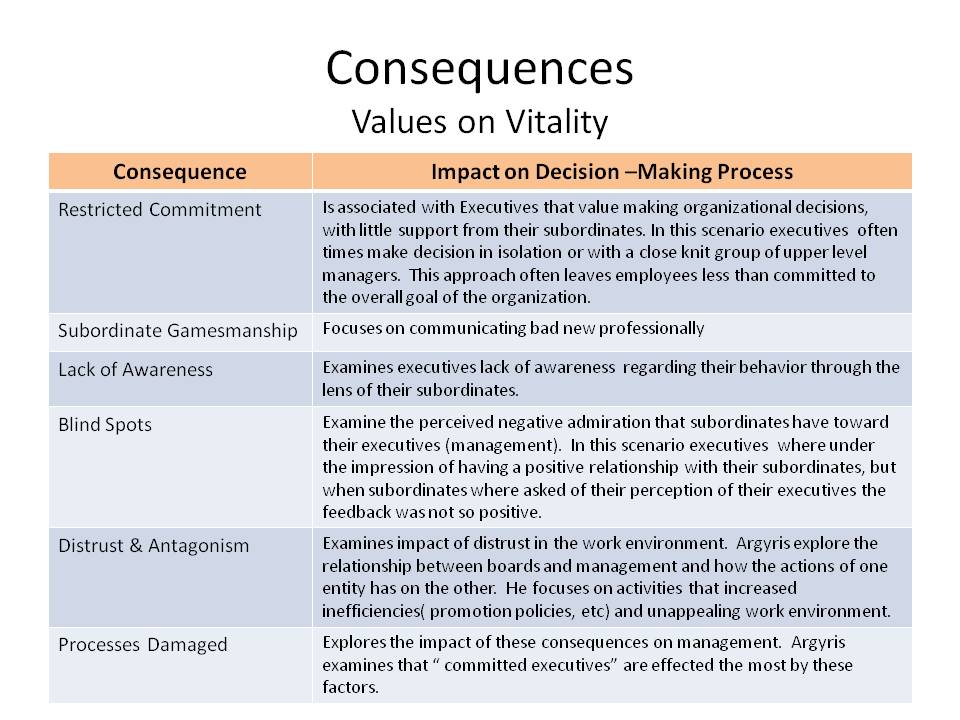

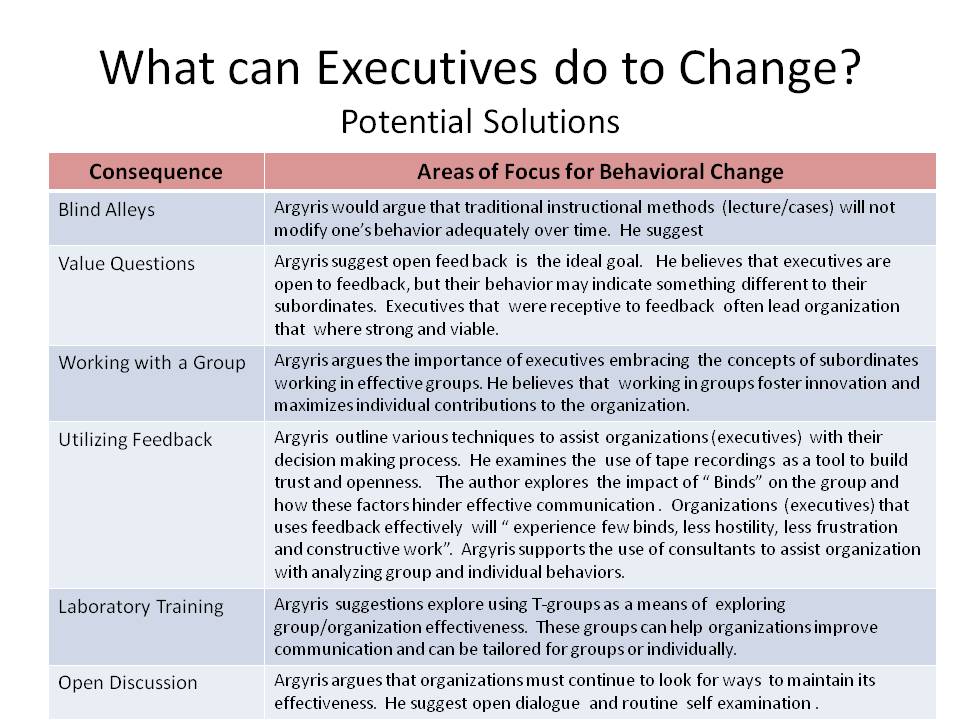

Argyris observed several decision making weaknesses and concluded that:

| Conclusion A |

Conclusion B |

Conclusion C |

Conclusion D |

| "The actual behavior of top executives during decision- making meetings often does not jibe with their attitudes and prescriptions about effective executive action." (Page 59) |

"The gap that often exists between what executives say and how they behave helps create barriers to openness and trust, to the effective search for alternatives, to innovation, and to flexibility in the organization." (Page 59) |

"... barriers are more destructive in important decision-making meetings than in routine meetings, and they upset effective managers more than ineffective ones"(Page 60) |

"... barriers cannot be broken down simply by intellectual exercises. Rather, executives need feedback concerning their behavior and opportunities to develop self-awareness in action. To this end, certain kinds of questioning are valuable; playing back and analyzing tape recordings of meetings has proved to be a helpful step; and laboratory education programs are valuable." (Page 60) |

|

Further Reading

|