|

Bolman & Deal: Chapter 9 Power, Conflict & CoalitionPolitical Assumptions (pp. 194-195)

- Coalition members have differences in values, information, information, and perceptions of reality.

- Most important decisions involve allocating scarce resources.

- Scare resources and differences in values put conflict in center of day-to day dynamics.

- Goals and decision making emerge from bargaining and negotiating among stakeholders jockeying for their own interests.

- Organizations are coalitions of individuals and interest groups.

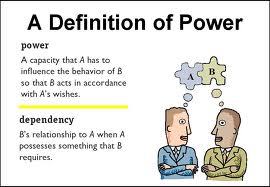

Implications of Political Propositions (p. 196)* Differences and scarce resources make power a key resource.

- Power is the ability to make something happen.Organizations as Coalitions (p. 198)* Cyert and March (1963) – Differences btwn structural and political views of goals.

- Confusion over wage payments (“costs”) and dividend payments (“profit.”)

- Makes slightly more sense to say that the goal of a business enterprise is to maximize profit than to say to say its goal is to maximize the salary of the janitor.Relational Conceptions (p. 200)Cyert and March (1963): Relational Concepts – rules to make decisions manageable.1) Quasi-resolution of conflict: Instead of solving conflict, the problem is broken up into smaller pieces for different units. Decisions never consistent, and only need to be good enough to keep the coalition functioning.2) Uncertainty avoidance: Orgs use a range of simplifying mechanisms (SOPs and traditions that enables them to act as if the environment is clearer than it is.3) Problemistic search: Organizations look for solutions near the presenting problem and grab the first acceptable solution.4) Organizational learning: Over time, organizations evolve their goals, altering what they attend to and what they ignore.Power and Decision Making (p. 201)* Alliances form b/c members have common interests. Can do more together than apart.

- Human Resource theorists: Less emphasis on power and more on empowerment. - Power typically viewed as negative. In reality power produces results.Authorities and Partisans (p. 201)* Participation, openness, and collaboration substitute for power.

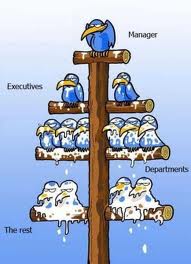

- Gamson (1968) – Relationship btwn antagonists – partisans and authorities.

- By virtue of their position, authorities are entitled to make decisions on their subordinates.

- Authorities are the recipients or targets of influence, and agents of social control. (Ex: Parents function as authorities, children as partisans. Parents make decisions, but children try to influence the decision makers.)Sources of Power (Baldridge, 1971; French & Raven 1959, Pfeffer, 1981) (p. 203)* Position Power (authority): Positions confer levels of legitimate authority.

- Control of Rewards: Ability to deliver jobs, money and rewards brings power.

- Coercive: Rests in the ability to constrain, block, interfere or punish.

- Information & expertise: Power flows to those with the info and know how.

- Reputation: builds on expertise. Track records based on prior performance.

- Personal Power: Attractive and social adept b/c of charisma, energy and vision.

- Alliances/Networks: Getting things done involves working in complex groups.

- Access & Control of agendas: By-product of alliances/networks is making agendas.

- Framing: Elites can convince others to support things not in their best interest. Distribution of Power - Alderfer (1979) and Brown (1983)(p.205)* Overbound: Power is highly concentrated, everything is tightly regulated.

- Underbound: Power is diffuse and the system is loosely controlled. Conflict in Organizations (p.206)* Combination of scares resources + divergent interests = conflict.

- Conflict is not always a problem or sign that something is amiss.

|

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

|

|

Morgan: Chapter 6 Interest, Conflict & PowerOrganizations as Political Systems(pp. 149-151)

- Organizations are intrinsically political.

- Politics and politicking are an essential aspect of organizational life and not necessarily an optional and dysfunctional extra.

- Utilizing the lens of organizations as systems of government, aids in uncovering the politics of organizational life and garner vital organizational qualities that are often glossed over or discounted.Organizations as Systems of Government (pp. 151 – 156)* When an organization functions like a government, a particular system of “rule” is embraced in order to maintain and regulate employees. Though many hold the belief there ought to be clear separations between business and politics, organizations typically implement more than one type of rule. Within this mixed approach, one rule serves as the dominate and then is coupled with facets of other systems.

- In an autocratic rule– the power to shape action and decision making rests in the hands of an individual or a group. Managers wield substantial power stemming from personal characteristics, family ties, or skill in cultivating influence and prestige within the organization.

- In a bureaucracy – power and accountability are closely linked with an individual’s knowledge and usage of the rules.

- In a technocracy – power and accountability are specifically linked to an individual’s technical knowledge and expertise. The pattern of power is often in flux as it and the individuals/groups rise and decline in concert with their technical contributions.

- In a representative democracy – the power to rule rests with the populace who elects representatives to act on their behalf

- In industrial codetermination – serves as a coalition where owners and employees codetermine the organization’s future through the process of shared power and decision making. This type of rule has not eagerly embraced by members of the labor movement due to participating as part of the decision making process limits an individual’s right to oppose a decision made.

- In industrial (direct) democracy- Equal right to rule and to the decision making process lays in the lap of all (employees and managers). A hindrance noted is employees decision making ability is limited to minor issues and they are excluded from the major ones.

- Political choice underpins organizational choiceOrganizations as Systems of Political Activity (pp.156- 163)* The need for organizational politics arises when a diversity of tensions emerges among individuals who think and act differently

- Organizational politics can be systematically analyzed by examining the relations between: interests, conflict, and power.

- Interests – are areas of concern and individual desires to preserve, enlarge, achieve, or protect. This would also encompass goals, values, desires, expectations, and orientations/inclinations influencing an individual’s behavior. There are three interconnected domains that determine an individual’s interest: Task (one's job); Career (job aspirations); Extramural (values, beliefs, personality, lifestyle)

- Many experience degrees of overlap between competing aims and aspirations which structure their task in such a way allowing achievement of all their aims at once. Whereas others have to find contentment through compromise.

- Interests unraveled expose underpinning intent and motivation factors. Utilizing the political metaphor creates the view of organizations as loose networks of people with opposing interests gathered together for the sake of expediency. This formal/informal group of people is called a coalition.

- An important dimension of organizational life is coalition building. This is achieved by managing a balance between the rewards and contributions needed to sustain membership.

- Coalition development is a strategy an individual can use to advance personal interests within the organization. When given considerable attention the individual increases the degree of power and influence wielded.Understanding Conflict (pp. 163 - 166)* Whenever divergent interests are present so is conflict. Conflict can stem from an array of areas such as: personal, interpersonal, coalitions, scarcity of resources, organizational structures and the like.

- Conflict fuels the system of organizational politics through competition and collaboration. By pitting collaborative groups against one another to compete for limited resources, status, and career advancement a sense of gamesmanship is fostered. This can be seen in organizations, office settings, and horizontal relations.

- Outcomes from these combative situations can lead to personality clashes, hidden agenda, and resentment. The organizational culture can be impacted and institutionalized attitudes, stereotypes, values, belief, rituals can be embedded. Exploring Power (pp. 166 – 194)* Though a clear definition has not emerged, many organizational theorist look to Robert Dahl, American political scientist, who posits power is the ability to get an individual to do something that the individual would not have done.

- When conflicts rises power is the vehicle which brings resolution. There are varied sources of power and their usage shapes organizational life dynamics.

- Three types of formal authority are charismatic (special qualities), tradition (monarchs), and rule of law (bureaucratic). In most organizations, formal authority is bureaucratic.

- Formal authority is only effective to the extent it is legitimized from the base of the organization.

- In order for organizations to thrive, there is a continual need for resources (scarcity or limited access to). The ability to allocate resources within or between organizations establishes resource power.

- The use of organizational structure, rules, regulations, and procedures are tools to aid in improving task performance. It can also be used based on political motivation to either minimize or expand individual’s roles and influence.

- Rules and regulations can be a double edged sword. What they were created for can be used to block their implementation.

- There are three interrelated elements when discussing control of decision-making process. They are: decision premises (at the foundational level hampering agendas through deflection), decision processes (ascertaining if a decision can be taken), and decision issues and objectives (determine what’s to be addressed and the evaluation criterion).

- Control of knowledge and information fosters individuals to be “gatekeepers” and through filtering information disseminated member’s perception are influenced and organizational reality are shaped. As a “gatekeeper” an individual is rendered indispensable and maintains “expert” status.

- Control of boundaries entails “boundary management” between the different elements of an organization. A sustainable degree of power is built by monitoring and controlling boundary transactions. This can be seen between different work groups/departments or between an organization and its environment.

- The ability to cope with uncertainty can give technical experts or troubleshooters power, whether the uncertainty is environmental (e.g., markets, sources of raw materials, or finance) or operational (e.g., breakdown of machinery or data processing). Personnel who have the authority or expertise to respond to inevitable uncertainty can accrue power by promoting themselves as indispensable.

- Control of technology shapes organizational relationships and interdependence, and introducing new technology can have serious consequences for the balance of power. In organizations that use sequential technology, such as an assembly line, any one unit has the power to disrupt the whole. In organizations that work in autonomous units, this power of one individual or unit to disrupt the operations is much more limited.

- Interpersonal alliances and networks create an “informal organization” in which individuals exchange information with colleagues, via personal friendships or participation in professional groups, for example. Individuals who are successful in building informal coalitions of like-minded people can wield influence and power, and can even be perceived as gatekeepers to their factions.

- Counterorganizations, such as trade unions, exercise “countervailing” control by serving as a check against the dominant organizational power structure. Consumer associations and social movements attempt to “countervail” the influence of corporate interests on government.

- Leaders exercise symbolic management in three key ways: imagery, theater, and gamesmanship. A leader may use vivid metaphors or storytelling to inspire an image of success. He or she may use theatrics, such as the appearance of their office or a style of dress to convey an image of power. They may also approach their organization as a game of strategy, and will employ tactics ranging from intimidation to the granting of rewards to achieve their ends.

- Gender and our perceptions of it have a strong influence on power in the workplace. Women have faced many challenges in advancement due to the “glass ceiling” that has denied them promotions and the lack of access to the “old boys’ network” which wields informal power. Organizations have historically been encouraged to be rational, assertive, and strong -- characteristics that are stereotypically attributed to men. Women are stereotyped as intuitive, emotional, and nurturing -- characteristics that are becoming more valued in modern organizations. Both gender roles and the models for successful organizational leadership are in flux, and therefore there are numerous strategies women and men may employ to gain personal power within an organization.

- A paradox of power is that people at all levels of an organization often describe themselves as feeling powerless. Therefore, it is helpful to consider deep structural factors that define perceptions of power. A CEO may find their power constrained by the broader economic factors that influence an industry. Likewise, there are significant elements of our culture such as race, class, and education that may shape one’s own perceived power within an organization.

- The power one already has can grow by exchanging information and opportunities with others. As someone begins to feel empowered to achieve their dreams, their power can become become self-perpetuating.

- Although the elements above comprise a thorough overview, there remains ambiguity about power. Questions remain, for example, is power structural or interpersonal? Is manifest or potential power more important? Managing Pluralist Organizations (p. 194-202)

- The metaphor of an organization as a political system primarily applies to organizations that use a “pluralist” frame of reference, as opposed to a “unitary” or “radical” frame of reference. These frames of reference can be useful analytical tools and/or can help managers develop organizational ideologies that will help meet their particular goals.

- Unitary - Common objectives and goals, well integrated team; conflict is rare and transient, attributed to troublemakers; power is largely ignored as a concept, leadership guides toward common interests.

- Pluralist - Diversity of interests, loose coalition; conflict is inherent and can be productive; power is derived from a variety of sources and is crucial to resolving conflicts.

- Radical - Rival forces strive for largely incompatible ends; conflict is always present and will eventually lead to wide structural change; power is unequal, reflective of society at large.

- Unitary managers tend to use formal power and cultivate sense of direction among all employees. Unitary managers try to avoid political realities and conflict.

- A pluralist manager may try to encourage productive conflict for the purposes of creativity. Pluralist managers must constantly analyze interests, monitor conflicts, and explore power relations.

- A pluralist manager may look to five styles of handling conflicts, depending on their preferences for being assertive and cooperative:In radical organizations, disputes need to be negotiated in fairly formal terms, and a “winner-take-all” mentality is prevalent.

- Avoiding - ignoring or postponing management of a conflict

- Compromise - negotiating, looking for trade-offs

- Competition - creating rivalry or win-lose situations

- Accommodation - giving up or submitting

- (p. 202-206)

- Organizational politics has become a taboo subject, due to the ideal that the goals of the organization should take priority over personal objectives. However, a political analysis is critical to our understanding of the key sources of power within an organization. It helps us understand why organizations do not always behave as rational, functionally integrated systems. It can explain how employees are motivated by proximity or access to power. It also allows us to examine the role that organizations play in the larger society.

- However, use of the political metaphor exclusively can lead to the tendency to view an organization very cynically, assuming hidden political agendas everywhere. In addition, it may overstate the power of individuals at lower levels of an organization and understate the significance of those who hold the ultimate decision making authority for setting its course.VIDEO: Igor Popovich, Director of the Career Professional Australia organization, offers some advice on "How to Get What You Want" with power in negotiation. Think about the various sources of power that he discusses in negotiation settings. Also, admire his shiny vest and his reaction when his phone rings at the 4-minute mark. He seems like an interesting fellow.

|

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Significant Sources of Organizational Power

- Formal authority

- Control of scarce resources

- Use of organizational structure, rule, and regulations

- Control of decision process

- Control of knowledge and information

- Control of boundaries

- Ability to cope with uncertainty

- Control of technology

- Interpersonal alliances, networks, and control of “informal organization”

- Control of counterorganizations

- Symbolism and the management of meaning

- Gender and the management of gender relations

- Structural factors that define the stage of action

- The power one already has

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

|